Couple Art I Trust You Facing Away From Each Other Art

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: Portrait of a complex marriage

(Image credit:

Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017

)

Mexican artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera painted each other for 25 years: those works give us an insight into their human relationship, argues Kelly Grovier.

Due south

Seen side-by-side in photographs, they struck an almost comic pose: his girth dwarfing her petite frame. When they married, her parents called them 'the elephant' and 'the dove'. He was the older, celebrated master of frescoes who helped revive an ancient Mayan landscape tradition, and gave a vivid visual vox to indigenous Mexican labourers seeking social equality after centuries of colonial oppression. She was the younger, self-mythologising dreamer, who magically wove from piercing introspection and chronic concrete pain paintings of a severe and mysterious beauty. Together, they were two of the almost of import artists of the 20th Century.

When Kahlo and Rivera married, her parents chosen them 'the elephant' and 'the dove' (Credit: Alamy)

When it comes to telling the story of the complex relationship between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, historians invariably reach for the aforementioned ready of biographical soundbites: his early career in Paris in the 1910s as a Cubist and her childhood struggles with polio; their fleeting first acquaintance in 1922 when she was only 15 and he was 37; the bus blow three years later that shattered her spine, pelvis, collarbone and ribs; her discovery of painting as salvation while she was bedridden and recuperating; their re-acquaintance in 1927 and his early awe at her talent; his affairs and her abortions; their divorce in 1939 and remarriage a year later.

Portrait of the artists

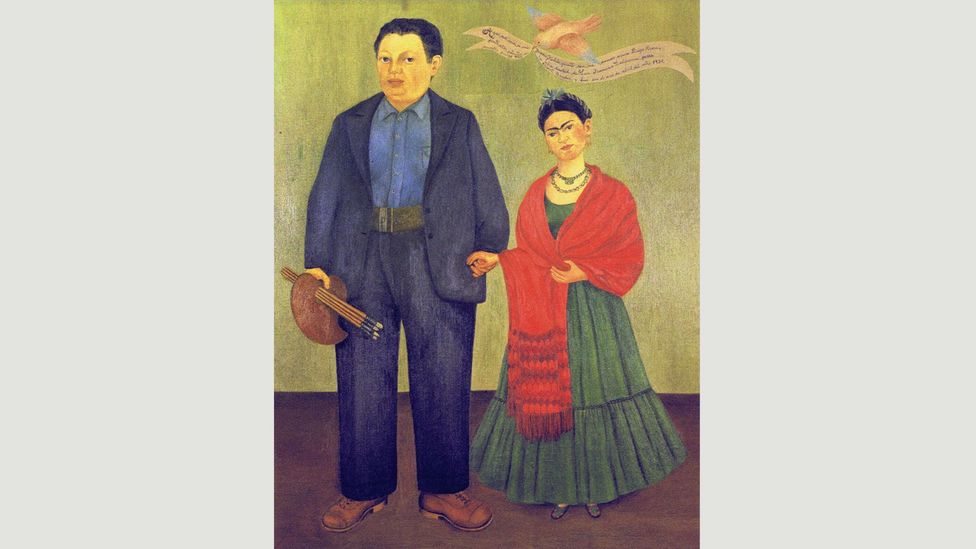

Simply if y'all really want to comprehend the passions and resentments, adoration and pain that defined the intense entanglement of Kahlo'southward and Rivera's lives, stop reading and showtime looking. Everything you need to know is there in the mode the 2 artists portrayed each other in their works. Take Frida and Diego Rivera (1931), the famous double portrait she painted two years afterwards they married for the outset time in 1931, when the couple were living in California's Bay Surface area.

This 1931 portrait by Kahlo is hardly the pic of simple marital bliss (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017)

Though the ribbon pinched in the bill of the pigeon that hovers in the top correct of the painting may joyously declare "Hither you see us, me, Frieda Kahlo, with my beloved hubby Diego Rivera", this is hardly the moving-picture show of uncomplicated marital bliss. With its criss-crossing, out-of-sync stares and slowly unclasping easily, the sail vibrates with subtle tensions. The relationship it depicts is anything merely straightforward or easily captioned.

What are we to make of the slight swivel of Diego'south caput, forever away from hers, while his eyes migrate dorsum similar a compass's needle in Kahlo's management? What can we get together from the cockeyed, quizzical tilt of her own gaze, fixed as information technology is in dead space somewhere to our left, refusing either to run in parallel with his or engage ours? How do we read the curious clash of sartorial styles – his European suit and her traditional Mexican dress? Though Kahlo painted the work, why is information technology that we find Diego clutching the palette and brushes, every bit she grips a knot at her stomach with one paw and, with the other, begins to allow go?

A wedlock of inconvenience

The portrait was undertaken when Kahlo accompanied Diego on a lengthy sojourn to San Francisco, where he had been deputed to create murals for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California Schoolhouse of Fine Art. The epitome captures Kahlo, who had adopted traditional Mexican dress to impress the champion of the Mexican worker, at a key moment in her evolution. The fist she makes at her gut – her fingers wringing a wad of shawl – may be an innuendo to the chronic uterine hurting she'd been suffering the past six years, since the handrail of a bus she was on in United mexican states City ripped through her torso, leaving her in recurring agony. Merely the gesture is as well prescient of the losses she'll experience past ensuing miscarriages and disability to carry a child to term. As a foreshadow, the gesture rhymes with the wandering eyes of the two subjects, who volition each both keep to have a string of extramarital affairs.

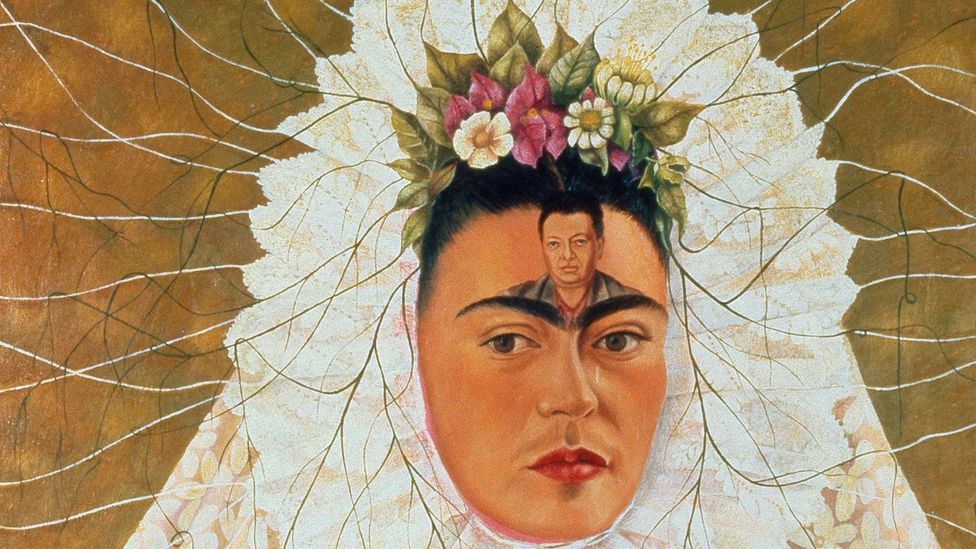

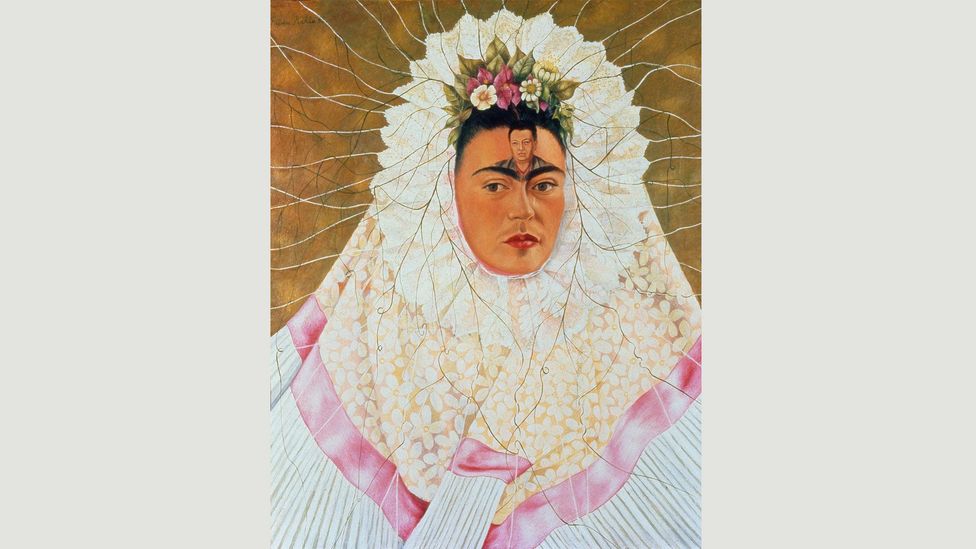

Self-Portrait as Tehuana (1943) is oft referred to as 'Diego on my listen' (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017)

A decade afterward painting Frida and Diego Rivera, Kahlo volition revisit the subject of their tumultuous relationship in one of her near haunting cocky-portraits – a genre of which she would become every bit potent a pioneer as Rembrandt and Van Gogh earlier her. Self-Portrait equally Tehuana (1943) (often referred to as 'Diego on My Mind'), was begun in 1940, during the cursory interlude between the couple's 2 volatile marriages. It shows the artist clad in the lace of traditional Mexican dress, surrounded surreally by a shatter of web-like fibres that appear to scissure the piece of work's invisible pane, as if the windscreen of her spirit has been struck by an existential stone.

At the centre of the impact is a miniature bosom of Diego, emblazoned on her forehead similar an elaborate third eye – a recurring motif in folk art symbolising inner vision. The migration of Diego from an imposing physical presence beside her in the earlier, more conventional portrait, to an integral component of her very being, is profound. Withal tempestuous their human relationship has become, she has come up to see Diego as the very lens through which she perceives reality – the epicentre of her creativity.

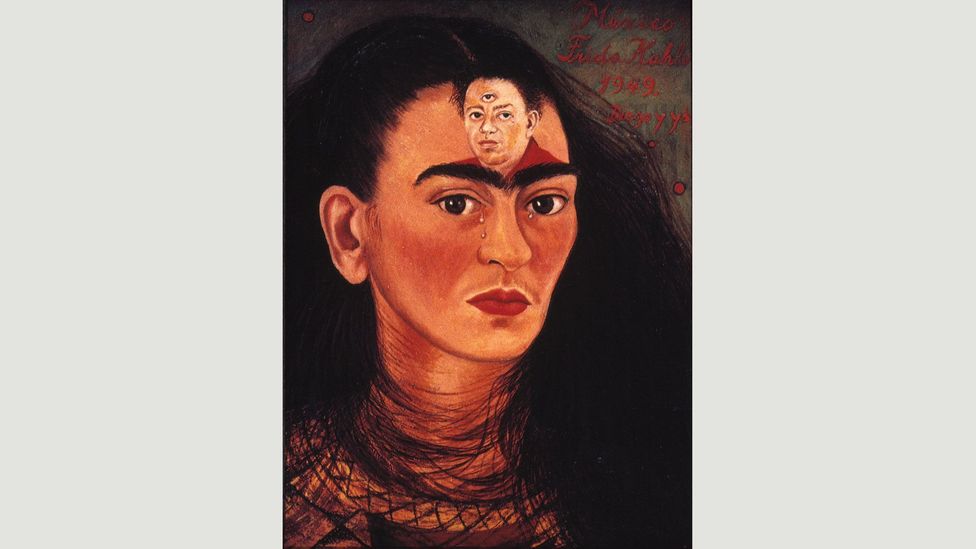

Diego and I (1949) was created among rumours that Rivera would soon abandon her (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017)

A after self-portrait, Diego and I (1949), revisits the theme of Diego imprinted on Kahlo'due south brow and was created amid rumours that he would soon abandon her for a Hollywood starlet. The trails of tears that streak Kahlo's cheeks invest the face-within-a-face with a gaping wound-like trauma – a stigmata of the mind.

An unflinching gaze

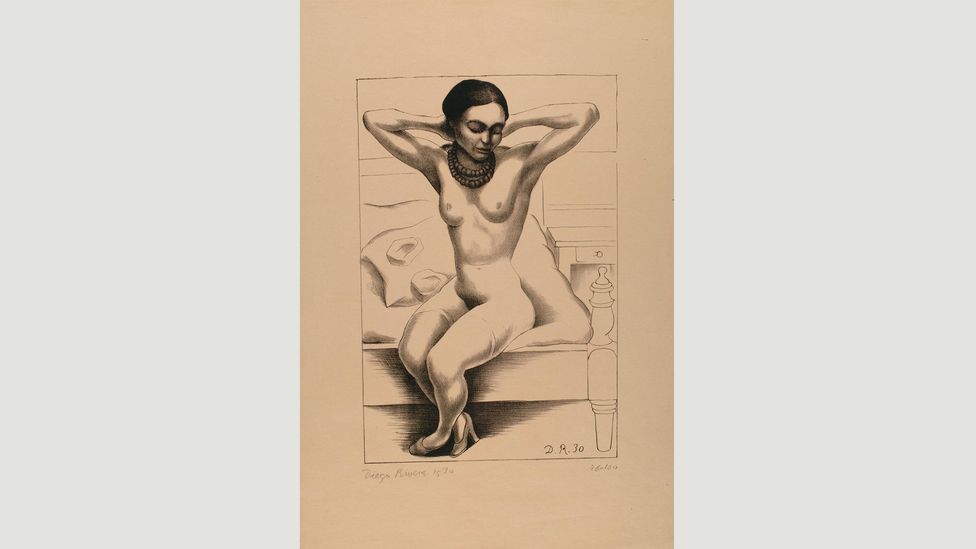

Unlike Kahlo, for whom painting her married man'south face was a frequent cartographic exercise that enabled her to map the undiscovered territories of their love and art, Rivera rather less frequently captured Kahlo's likeness in his work. His intimate etching, Seated Nude with Raised Artillery (Frida Kahlo), created in the couple'south first year of marriage in 1930, is lovingly observed. Sitting on the edge of their bed with nothing left to take off but her stockings, heels, and a mesomorphic necklace, she appears lost in contemplation as she reaches backside her head to untie her hair. Rivera has frozen her in a moment of seemingly fretless repose, her elbows hoisted high like butterfly wings about to lift.

Rivera made Seated Nude with Raised Arms (Frida Kahlo) in the offset year of their matrimony (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017)

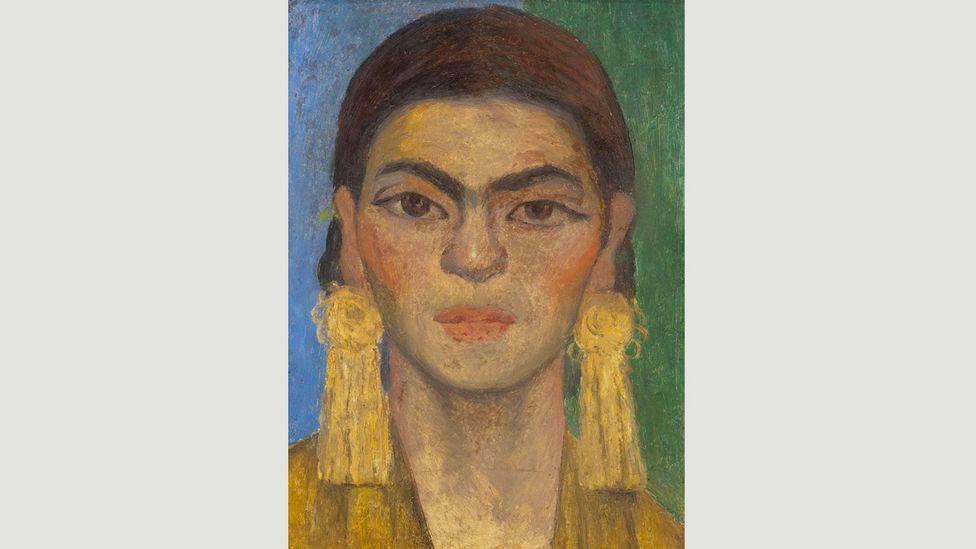

9 years afterwards, that innocent sense of placidity has sharpened into something rather more severe with the creation past Rivera of Portrait of Frida Kahlo (1939) – described by the institution that owns information technology, the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as "the just known easel portrait of his wife". Set up against a riven sky that shifts dramatically from blue on the left to light-green on the right, Kahlo'due south unflinching stare is uncomfortably piercing in its hypnotic hold.

Rivera painted this portrait of Kahlo in 1939, and held onto it until his death in 1957 (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, United mexican states, DF/DACS 2017)

The penetrating likeness has the intensity of an ancient icon and ably embodies Diego'due south famous assessment of Kahlo'south genius, as possessing "a merciless yet sensitive power of observation". The modest (14 × 9 .75 in. / 35.56 × 24.77 cm) prototype, which Diego held onto like his own Mona Lisa until his death in November 1957, represents the main muralist'south effort to see Kahlo through Kahlo's own eyes. His decision to paint the portrait on asbestos shingle invests the work with a secret poignancy and suggests the alternatingly insulating and toxic nature of their dear.

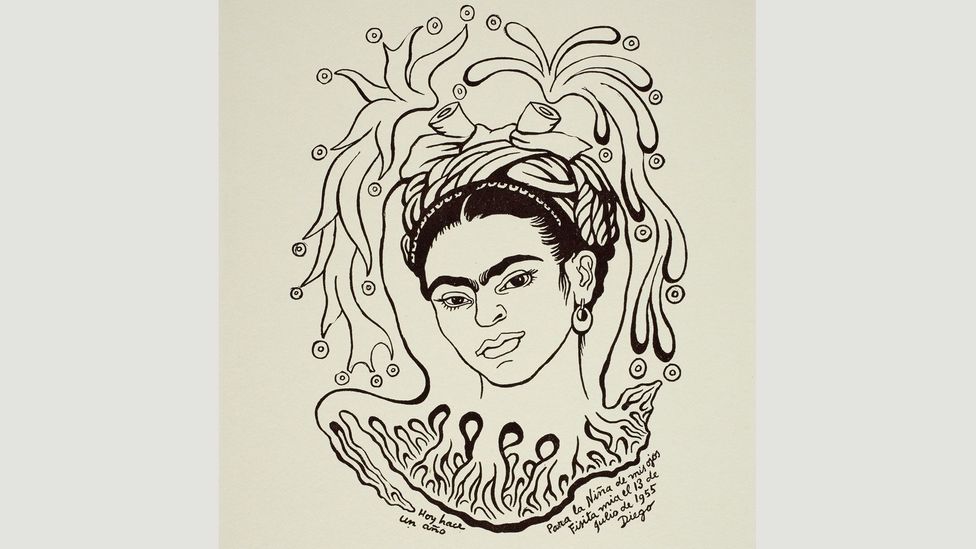

Burn, as a resonant symbol for Kahlo's spirit, will go along to ember in Rivera'south mind even subsequently her premature passing in July 1954 at the age of 47, following a bout with gangrene a year earlier that had resulted in her leg being amputated. To mark the anniversary of her expiry, the widower drew a portrait of his wife that manages to transform her image into a kind of inscrutable Sphinx – an esoteric icon.

This drawing was made past Rivera a year after Kahlo'southward decease at the historic period of 47 (Credit: Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, DF/DACS 2017)

Based on a moving picture taken 16 years earlier by a photographer with whom Kahlo was having an thing, Rivera's drawing locates Kahlo's countenance at the epicentre of tensions between primal energies – earth and fire. Framing her cocked caput is a coil of ribbons that have swollen surreally into sputtering arteries, while below her chin a foreign strangle of gnarled roots flex. That clash of interior and exterior forces – heart and copse – almost distracts us from the unexpected sweetness of the uncomplicated sign-off that Rivera has inscribed below her: "For the girl of my eyes".

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Civilisation, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If Y'all Only Read six Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Time to come, Earth, Civilization, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171204-frida-kahlo-and-diego-rivera-portrait-of-a-complex-marriage